- Home

- Maria Genova

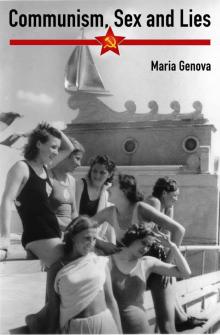

Communism, Sex and Lies

Communism, Sex and Lies Read online

Communism

Sex and

Lies

Maria Genova

Maria Genova: Communism, Sex and Lies – novel. First published in the Netherlands in 2007.

Key words: Communism, Communist manifesto, Eastern Europe history, Russian historical fiction, Sexual awakening, Coming of age.

© 2017 Maria Genova, Email: [email protected] and Morton International Publishing

Translation and Publishing: Caroline Morton-Gallagher, Morton International Publishing. Email: [email protected]

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photo print, microfilm or any other means, without written permission from the author.

Content

The unreal reality

The sexy enemy of the people

A packet of butter

The meaning of life

In the elite prison

Shooting with Kalashnikovs

Fireflies and discrimination

Travelling with a secret weapon

The magic of winter

Unexpected meeting

Russia

Gorbachev

Surprise attack

Lies

Fainted

Western tourists

In love with a corpse

From communism to capitalism

A glass tower of prejudices

Dog food and diaries

On top of the world

Note from the author

Acknowledgments

The unreal reality

I looked at my wedding ring somewhat incredulous. The three diamonds sparkled beautifully in the bright sun. Married in Las Vegas, in the lair of capitalism. If anyone had predicted this a few years before, I would have said they were crazy. Back then we couldn’t even leave our country and all Bulgarian media portrayed The West as hell on earth. That seemed so long ago now. Perhaps because communism was such a surreal experience. We were taught pseudo history and were silenced from a very early age. It was for that very reason that my generation did not believe that the ideals on which we were raised would so quickly land on the dumping ground of real history. We felt free and happy in our spacious cage, in a country where nothing was allowed and everything was tolerated. We enjoyed our carefree life without our own responsibilities, because communism was in control. We had plenty of time to party, to flirt or to stand in line to pick up the latest scarce product.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall my eyes were opened. Communism was suddenly an incomprehensible paradox. I had helped build a just society, one I tried to dismantle with just as much dedication a few years later. Despite everyone knowing there was no way back, many people started to feel nostalgia towards the good old days, where you didn’t need to worry if you could put enough bread on the table or that you would lose your job. They didn’t want communism to live on in the memories of generations as just a cold dictatorship, because underneath the cold surface hid much optimism, humour and good ideas.

I found nostalgia towards the past to be completely useless, because no one could bring it back to life. My youth became an unreachable island in time. Only in my thoughts could I still be that innocent girl that sang communist songs with such fervour. Only in my thoughts could I see myself as the sexy, rebellious teenager, who tried to win the hearts of young men. In reality, the girl has blossomed into a woman, a woman with a past. She could not forget that, because the Bulgarian communists were the most skilled designers of the soul.

While I admired my expensive diamond ring I wondered for a second whether the entire wedding in Las Vegas had actually taken place. The communists had made us believe in things that didn’t exists and denied those that did. Was I so brainwashed that I also could not distinguish fairy tales from reality?

Memories swam like tiny lost fish towards the surface of my consciousness. As communist youth, we were probably the neatest because we had to endure a weekly inspection at school. Every Monday the teachers would look at our nails and if they felt they were too long they would cut them short right there. A teacher disapproved of my hairdo, grabbed a large pair of scissors from her desk drawer and started cutting. I thought it pretty normal that my hair was cut in front of the class and I was not embarrassed. I was more worried about the result, but because there was no mirror I could not see. The only thing I heard during those endless minutes was the tsjik-tsjik sound. The blunt scissors caught in my thick hair a few times, but eventually all undesired hair fell on the floor.

During the break, all the other kids were remarkably quiet. No one dared to comment on my new hairdo. After a while the biggest bully came towards me. ‘Mer, you have quite an original look’, he said. ‘Like a cabbage run over by a Trabant’.

‘Why don’t you go and say that to Comrade Dimitrova’, I snapped. ‘Then you might be given an even more original look. If you’re too chicken, I can arrange it for you’. The bully backed off just as quickly as he had appeared before me.

When I got home my mother nearly had a heart attack. ‘What happened to your hair?’.

‘Comrade Dimitrova thought it was too long,’ I replied. ‘Has Comrade Dimitrova gone blind? Your hair was no longer than shoulder length!’

‘She didn’t think my hairdo was neat enough’.

My mother was outraged. She always thought she could cut my hair well and now her creation had been publicly disapproved of. Despite this, she did not go to complain, because you just didn’t do that. You never argued with teachers, civil servants or party secretaries. The people did what the party leaders commanded and adhered to thousands of unwritten rules. No wonder that during my time communism had become so accepted: the older generation had been completely brainwashed and the new generation inherited a tightly controlled thought pattern.

The most important school rule was that you were not allowed to forget your silk communist scarf. All teachers were very strict about this: without the red scarf, you were not allowed in school. It did not matter how far away you lived from school, you had to go back home to get it. And if your parents were out to work then you had to phone them to get them to come as soon as possible.

We were not bothered with all the rules. It was all daily routine and only now and then did things go wrong. My grandmother has knitted a lovely white collar as replacement for the cotton collar of my uniform. I had to leave the school premised immediately, because such deviations were not tolerated in a country where all citizens were to be alike.

Some teachers with dictatorial tendencies had the habit of pulling disobedient children through the classroom by their ears. One always threw pencils through the window if he became angry, another hit us around the ears with a ruler and threw chalk at us. The same teachers gave us lessons in ethics in order to become better citizens. We had to repeat in unison what we would do if we saw an old woman with a heavy shopping bag. ‘Ask the woman if we can carry her shopping home for her’, we repeated obediently. And if a mother with a child boarded a full bus? ‘Stand up and ask if she wanted to sit down’, was the answer.

I personally hated Comrade Popova the most, a teacher who wore a gold ring. If I wasn’t paying attention she would tick it against my head. Sometime Comrade Popova thought that half the class was not behaving and sent us all to the corner. As there were not that many corners, we would form lines along the wall. We would stand with our backs to the class, look at each other and try not to laugh, because that would only make things worse. We didn’t want any remarks about bad behaviour in our school reports.

To get revenge on such tyrants, we would ‘disable’ their chairs by unscrewing bolts and moving the seat a little. We would laugh out loud if such a smug tyrant thudded onto the floor. ‘Who did this?’ was of course th

e inevitable question. We never ratted each other out. The lessons in ethics seemed to have some value after all.

Most of us were happy in the artificially created vacuum of Bulgarian communism. We felt it obvious that this was the most just, solidary and fantastic society. Nearly everything was well organized and there were no serious threats from outside the borders. Even though America had nuclear weapons we were convinced we could defeat the enemy. After all, we had the most powerful ally in the world: mother Russia.

Because of the communist propaganda, we knew that our ideals were stronger than the empty materialism of the West. This why every year we exuberantly celebrated the day that the communists came to power. Thousands of us marched through the streets in rows, waving balloons and chanting patriotic slogans. The festive music swept us up. Just once did we hear sad sounds and everyone turned around surprised. We saw a few men carrying a black coffin, on which the word capitalism had been painted. That was the reason for the sombre music, western capitalism was being symbolically buried to make room for a shining communist future for all countries worldwide.

During the parade, there were a number of official union representatives from Western countries on the official tribune. To my great surprise, they did not wave to us. That they did not know how to behave towards us did not represent a problem: the next day they were shown waving on the front page of the newspaper. A friend of my father’s, who worked at the newspaper, told him that his superiors ordered him to Photoshop the foreigners waving their hands with a little bit of cut and paste work.

The communist party had created a super state that took care of use from the cradle to the grave. Free education, free healthcare, guaranteed employment, hardly any theft or breakins at all… On the three radio stations we received in Bulgaria, we heard almost on a daily basis how much better the life was in Eastern Europe compared to the West. Everywhere on the streets were signs with propaganda written on them and the portrait of our party leader Todor Zjivkov hung in every school and in all public places. The streets were named after heroes such as Marx and Lenin and we were proud of the achievements of the communist system. Those who could not thrive in such a society could only blame themselves. Such as the old man who usually begged on the steps of the church, probably because he would rather be drunk than sober. I often gave him some of my pocket money, but I never talked to him, because beggars were by definition scary in a country without any unemployed.

A job was created for everyone. The party was a master in creating unnecessary jobs. Not that anyone felt unnecessary, but in Bulgaria, as in other communist countries, the principle was upheld that of three labourers, one worked, the second supervised and the third caused problems. It was more rule than exception that people arranged all sorts of private issues during working hours. ‘Work ennobles man’ was one of the most well-known slogans. Even the school children had to experience this and that is why we were regularly sent to the farmers to help them with their harvest. We all received a personal invitation. On the front the words read ‘voluntary work for the fatherland’. On the inside, it said: ‘attendance compulsory on penalty of sanctions’. We were not sure what the sanctions were, but no one dared not turn up for the compulsory voluntary work.

Each year it was something different: plucking grapes, digging up potatoes, gathering peanuts…I had a particular dislike of the peanuts. My hands would turn pitch black and rough from rooting in the dirt, I got backache from bending down and when it rained, the field turned into a mud pool. The worst things were the high targets, which were practically impossible to achieve if you were doing this work for the first time. If you did not achieve the target you would receive a public reprimand from the comrade who supervised. To prevent this, we used to put a layer of dirt on the bottom of the bucket; that weighed much heavier than peanuts and the kilos quickly added up.

The harvest was an inexhaustible source of stories about how we would fill the bottom of the cherry crates with leaves, how we smeared toothpaste on the doorknobs of the comrades and the modern version of sending a telegram: setting a piece of paper alight between the toes of the biggest sleepyhead and wait until he received the message. The damage from this cruel game was limited: in the worst case, they would have some blisters and the sleepyhead would not be able to achieve their target.

´We stayed in the farmer´s houses and some class mates were delegated to the man who runs the village shop´, my friend Olga said. ´The boys came into his store, drank all his booze and pelted each other with the eggs they found there. Then they went to the village square and threw the remaining eggs at a communist monument. ´

We laughed out loud. An adult would have landed in jail for many years for such an act, but they could not incarcerate drunk school kids. They were simply expelled from school. And shaven bald. That way everyone could see they were dangerous criminals.

Olga’s parents were labourers, the class that was praised to the heavens. On television, we did not hear anything else other than that our labourers were doing so well. The best workers received medals with the inscription ‘Hero of Labour’ and the departments with the highest production rates won the coveted trophy. Their photos were hung next to the entrance to the factories.

The Bulgarian people passionately built on the communist ideal and did everything the Russian leaders expected from them, such as was expected from a good little satellite state. When the Russians revealed after Stalin’s death that the Great Leader had in fact been a killing machine, we could hardly believe this. We tried to soothe the pain of this discovery with jokes. Otherwise we could not process that the building of communism was at the cost of so many innocent loves. There was a joke about Stalin, who was called by the secret police with the question if he had found his lost pipe.

‘Yes, it was under the couch’, said Stalin.

‘That’s impossible!’ the policeman cried out. ‘Three people have already confessed to stealing your pipe’.

The sexy enemy of the people

The family I grew up in was only half-communist. I did not want to know about my mother’s bourgeois’ upbringing. Of course, she had told us that her father had been a land owner and that the communists had taken everything away when they came to power after the Second World War. She vividly remembered how as a little girl she chased the uninvited guests from the grounds with a stick. They just laughed at her, pushed her to one side and plucked all the fruit from the vegetable garden ‘in the name of the people’. It was a shame about the lovely home, the servants and the horse stables, but she had to share her wealth with the rest of the people.

My sister and I thought it was weird that my grandparents used to be so wealthy. Luckily, we had nothing to fear. Usually everyone from aristocratic or bourgeois origins were declared the ‘enemy of the people’, but our father was a party member with the best communist background one could wish for. That compensated the traces of ‘blue blood’ and we did not have to fear that we would be denied access to good jobs.

We lived in a house at the foot of a hill. On the top a giant granite statue of a Russian solder towered above us. Aljosha could be seen both during the day and at night time, lit up by strong spotlights, and could not be ignored. The granite soldier watched over us and was the symbol of mother Russia who protected us from the imperialist West. Everyone who arrived in Plovdiv could see the colossal statue looming.

Plovdiv, the second largest city in Bulgaria, was built on seven hills, but just this one had become the symbol of the city. The attractions on the other hills were in the eyes of outsiders less imposing: an old clock tower, a weather station, an open-air cinema and a 2nd Century Roman amphitheatre. The century old excavations proved that Plovdiv was one of the oldest European cities. Not that there was much to signify this, because most of the monumental buildings had been transformed into advertisements for the communist ideal. They were hung full with slogans and housed exhibitions of carefully selected events in history, which the communists did not have any qua

lms about. From the viewpoint of the hills, the city looked like a giant beehive. People would cross each other walking, cars, busses and taxis rushed in every direction, school kids with neat uniforms walked in straight lines, labourers went to the factories in the industrial zone. Somewhere in this giant beehive was the queen, the communist party, and the people tried to care for her and make her happy.

Most people instinctively knew who they could trust. I mostly used my pretty neighbour Olga as a sounding block. Olga was a few years older than me and she was my role model on how to handle men. She enjoyed life and did not want to settle down. Olga could permit herself this luxury, because she was very attractive, with pretty brown eyes, and long blond hair that reached to her waist. Even when she had to cut her hair because of the toppled paint pot, with her large breasts and skinny waist she still formed an object of desire for men.

Olga sold train tickets. At the central station in Plovdiv it was a mass of people coming and going. A train ticket did not cost much at all and it looked like for that reason everyone had taken to travelling. Olga was usually busy, but sometimes there were times when she did not have anything to do. This was when she would polish her long nails and if, at that moment, a customer would want to buy a ticket then he would have to wait until her nails had dried. During such a beauty break her eyes rested on someone who made her pulse go quicker.

‘He sat on a bench across from my counter and each time I did not have a customer I would hold his gaze’, Olga said. ‘Then I placed the ‘closed’ sign on the counter and walked past him provocatively.’

Olga knew how to do a sexy walk: straight back, breasts stuck out and swaying the hips so that her bum would draw the attention of a blind man. ‘Men look at us to see us, but we look at men to be seen,’ was Olga’s motto.

The attractive man looked at her in admiration and asked if he could buy her lunch.

Communism, Sex and Lies

Communism, Sex and Lies